Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

The Curiosity rover has made its most unusual find to date on Mars: rocks made of pure sulfur. And it all began when the 1-ton rover happened to drive over a rock and crack it open, revealing yellowish-green crystals never spotted before on the red planet.

“I think it’s the strangest find of the whole mission and the most unexpected,” said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “I have to say, there’s a lot of luck involved here. Not every rock has something interesting inside.”

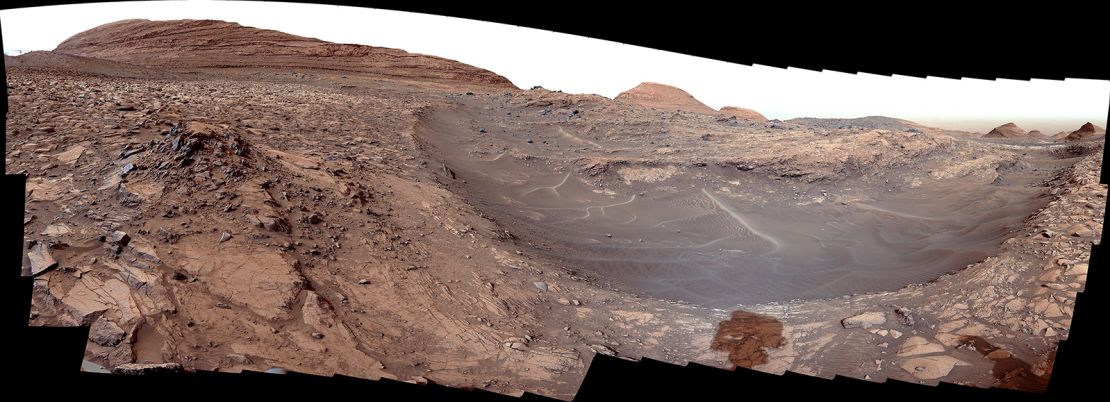

The Curiosity team was eager for the rover to investigate the Gediz Vallis channel, a winding groove that appears to have been created 3 billion years ago by a mix of flowing water and debris. The channel is carved into part of the 3-mile-tall (5-kilometer-tall) Mount Sharp. The rover has been scaling the mountain since 2014.

White stones had been visible in the distance, and the mission scientists wanted a closer look. The rover drivers at JPL, who send instructions to Curiosity, did a 90-degree turn to put the robotic explorer in the right position for its cameras to capture a mosaic of the surrounding landscape.

On the morning of May 30, Vasavada and his team looked at Curiosity’s mosaic and saw a crushed rock lying amid the rover’s wheel tracks. A closer picture of the rock made clear the “mind-blowing” find, he said.

Some of Curiosity’s discoveries, such as lakes that lasted millions of years and the presence of organic materials, have played into the rover’s ultimate mission goal: trying to determine whether Mars hosted habitable environments.

Now, scientists are on a mission to figure out what the presence of pure sulfur on Mars means and what it says about the red planet’s history.

A stunning find

Curiosity had already discovered sulfates on Mars, or salts that contain sulfur that are formed when water evaporates. The team has seen evidence of bright white calcium sulfate, also known as gypsum, within cracks on the Martian surface that are essentially hard-water deposits left behind by ancient groundwater flows.

“No one had pure sulfur on their bingo card,” Vasavada said.

Sulfur rocks typically have what Vasavada describes as a “beautiful, translucent and crystalline texture,” but weathering on Mars essentially sandblasted the outside of the rocks to blend in with the rest of the planet, which largely consists of shades of orange.

Members of the team were stunned twice — once when they saw the “gorgeous texture and color inside” the rock and then when they used Curiosity’s instruments to analyze the rock and received data indicating it was pure sulfur, Vasavada said.

Previously, while exploring Mars, NASA’s Spirit rover broke one of its wheels and had to drag it along while using the other five to drive backward. The drag of the wheel revealed bright white soil, which turned out to be nearly pure silica. The presence of silica suggests hot springs or steam vents may have once been on Mars, which could have created conditions favorable for microbial life if it ever existed on the planet.

The silica discovery is still one of the most important findings by the Spirit rover, which operated on Mars from 2004 to 2011. And Vasavada says it’s what inspired the team to “look behind” the Curiosity rover — otherwise they wouldn’t have seen the crushed sulfur.

“My jaw dropped when I saw the image of the sulfur,” said Briony Horgan, co-investigator on the Perseverance rover mission and professor of planetary science at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana. “Pure elemental sulfur is a very weird finding because on Earth we mostly find it in places like hydrothermal vents. Think Yellowstone! So it’s a big mystery to me as to how this rock formed in Mt. Sharp.”

A field of ‘strange rocks’

While approaching Gediz Vallis channel, Curiosity sent back pictures of an unusual sight: a flat area, about half the size of a football field, scattered with bright white hand-size rocks.

At first, the team thought the “strange rocks” were part of the debris from the channel, perhaps a layer that water had transported from higher up the mountain, Vasavada said.

But upon closer inspection, including the fortuitous crushing of the sulfur rock, the team now thinks that the flat, uniform field of rocks formed where they were found, he said.

The team was eager to take a sample of the rocks to study, but Curiosity couldn’t drill into the rocks because they were too small and brittle. To determine what process formed the sulfur rocks, the team considered nearby bedrock instead.

Pure sulfur only forms under certain conditions on Earth, such as volcanic processes or in hot or cold springs. Depending on the process, different minerals are created at the same time as the sulfur.

On June 18, the team sampled a large rock from the channel nicknamed “Mammoth Lakes.” An analysis of the rock’s dust, carried out by instruments within the rover’s belly, revealed a larger variety of minerals than ever seen before during the mission, Vasavada said.

“The running joke for us was we almost saw every mineral we’ve ever seen in the whole mission but all in this rock,” he said. “It’s almost an abundance of riches.”

Layers of Martian history

Since landing on Mars on August 5, 2012, the Curiosity rover has ascended 2,600 feet (800 meters) up the base of Mount Sharp from the floor of Gale Crater. The mountain is a central peak of the crater, which is a vast, dry ancient lake bed.

Each layer of Mount Sharp tells a different story about Mars’ history, including periods when the planet was wet and when it became drier.

Lately, Curiosity has been systematically investigating different features of the mountain, such as the Gediz Vallis channel. The channel was formed well after the mountain because it carves through different layers of Mount Sharp, Vasavada said.

After water and debris carved a trail, they left behind a 2-mile (3.2-kilometer) ridge of boulders and sediment below the channel. Although Curiosity arrived at the channel in March and is likely to stay for another month or two, it has been steadily climbing next to the debris trail for a while.

Scientists have wondered whether floodwaters or landslides caused the debris, and Curiosity’s investigations have shown that both violent water flows and landslides likely played a part. Some of the rocks are rounded like river rocks, suggesting they were carried by water, but others are more angular, meaning they were likely delivered by dry avalanches.

Then, water soaked into the debris, and chemical reactions created “halo” shapes that can be seen on some of the rocks that Curiosity has studied.

“This was not a quiet period on Mars,” said Becky Williams, a scientist with the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, and the deputy principal investigator of Curiosity’s Mast Camera, in a statement. “There was an exciting amount of activity here.

We’re looking at multiple flows down the channel, including energetic floods and boulder-rich flows.”

Scientists are eager to uncover more details, including how much water was present to help carve the channel in the first place.

Gediz Vallis channel has long been of interest to scientists, including Vasavada, who recalls looking at orbital images of the feature well before Curiosity landed on Mars.

“It’s always been something that’s just been really intriguing,” he said. “I remember when the rover kind of rolled over the final hill before we got to the channel, and you could all of a sudden see the landscape and the curved channel. Now, we’re actually here, seeing it with our own eyes, so to speak.”

Curiosity’s continuing journey

There’s no smoking gun pointing to how the sulfur was formed, but the team continues to analyze the data Curiosity collected to determine how and when each mineral formed.

“Maybe this rock slab has experienced multiple different kinds of environments,” Vasavada said, “and they’re sort of overprinting each other, and now we have to unravel that.”

Curiosity continues to explore the channel to look for more surprises, and after it moves on, the rover will head west to drive along the mountain, rather than straight up, to seek more intriguing geologic features.

Despite 12 years of wear and tear, including some “close calls” such as wheel issues and mechanical problems, Curiosity remains in great health, Vasavada said.

“I feel very lucky, but also we all feel cautious that the next one may not be only a close call, so we’re trying to make the most of it, and we have this landing site that’s been so wonderful,” he said. “I’m glad we chose something that was 12 years’ worth of science.”