Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

From deep in the Amazon rainforest, two dozen previously unknown pre-Columbian earthworks have been brought to light — and more than 10,000 such constructs may still be waiting to be discovered, according to new research.

Across the Amazon basin, rainforests spread their leafy boughs over millions of kilometers. In the ground far below the treetops are ancient, long-hidden remnants of human habitation. They are preserved as ditches, paths and wells, sometimes forming geometric patterns. Known as earthworks, they were shaped by indigenous peoples who lived in the area around 500 to 1,500 years ago.

Earthworks have been linked to ceremonial and defensive uses, and they offer a glimpse of what ancient settlements may have looked like.

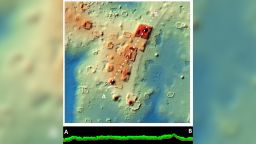

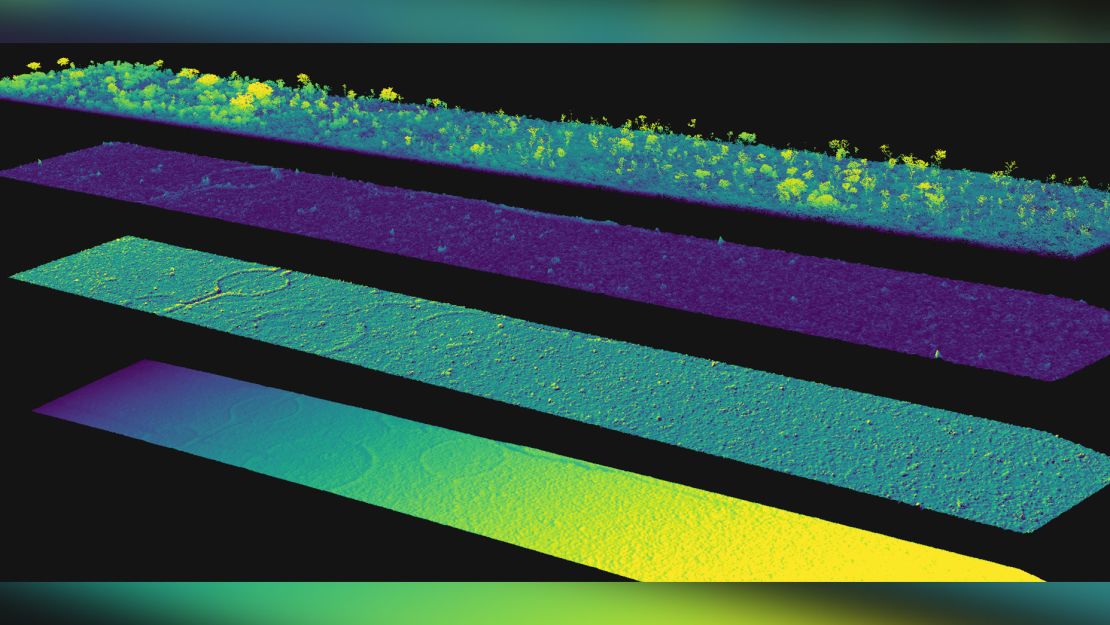

Many Amazonian earthworks that predate the arrival of European colonizers are revealed in deforested areas. But researchers suspected that there were even more such sites that are all but invisible today, concealed under dense foliage. To find them, scientists reviewed scans of terrain made with a remote sensing method called light detection and ranging, or lidar. This aerial technique pings the ground with laser pulses, measuring variations in distances to the ground. When the light rebounds, it’s combined with other data to generate 3D maps of the landscape below.

“Lidar is really essential to confirm the presence of the structures, especially beneath the forest,” said geographer Vinicius Peripato, a researcher at Brazil’s National Institute for Space Research in São Paulo. Peripatos is lead author of a study documenting the discoveries, published October 5 in the journal Science.

The study authors also evaluated decades of data recording tree species across the Amazon, searching for signs of species known to be managed and domesticated by pre-Columbian peoples. The new study incorporated the efforts of 160 researchers and data collected over 80 years, combining lidar and records of Amazonian tree distribution in predictive models that estimated where unknown earthworks might be found.

‘Far from pristine’

A notable aspect of the work is that it contributes to an emerging consensus that the Amazon “is far from pristine wilderness,” and that “Amazonian Indigenous history is as rich and dynamic as elsewhere,” said Dr. Michael Heckenberger, a professor of anthropology at the University of Florida. Heckenberger, who was not involved in the study, has conducted research in the Brazilian Amazon since the 1990s, working with indigenous peoples of the Xingu region.

“The conclusions are not surprising, but follow a trend in Amazonian studies to increase the scale, density and impact of human occupations on the Amazon forest,” Heckenberger told CNN in an email. These findings further demonstrate that the cultural heritage of indigenous peoples in the Americas and elsewhere is “remarkably dynamic and innovative,” he added.

At first, the authors weren’t sure whether the available lidar data would be useful for their project, Peripato told CNN. The scans were originally conducted to estimate rainforest biomass, so the resolution was lower than is typical for archaeological surveys.

“Initially, we were not sure if we would find anything,” Peripato said. “It was kind of a gamble that fortunately paid off.”

WATCH: Amazon tribes are using drones to track deforestation in Brazil

Beneath the canopy

Analysis of the lidar data revealed 24 previously unknown earthworks in spots scattered across the Amazon basin. These sites included a town with a plaza and a fortified village in the south; megalithic structures in the north; and rectangular and circular shapes, or geoglyphs, in the southwest.

The area covered by lidar represented just 0.08% of the Amazon rainforest, which spans approximately 2.6 million square miles (6.7 million square kilometers). “But since the extent of the Amazon is so big, we can’t just fly lidar over everything,” Peripato said.

To accurately predict how many more unseen earthworks might exist, the team’s computer model needed a lot more data. So the scientists also mapped 937 known earthworks, instructing the model to highlight locations for potential earthworks that shared similar topographic features with previously detected sites.

The researchers further narrowed down the list of possible hidden sites using tree survey data from 1,676 forest plots, looking for appearances of any of the 79 species that were known to be domesticated and cultivated by pre-Columbian cultures.

The model estimated that there are likely more than 10,000 and possibly more than 23,000 earthworks lurking beneath the Amazon’s canopy. The finding suggests that known sites make up no more than 9% of what may be preserved under Amazonian rainforest cover.

This undertaking stands out not only for its conclusions, but also because it involved numerous Brazilian experts, which isn’t the case for many other Amazon-related projects, said Dr. Juan Carlos Fernandez Diaz, a research assistant professor in the department of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Houston. Participation of local scientists “is something that needs to be celebrated, encouraged and supported by the media and the broad academic community,” Fernandez Diaz, who was not involved in the study, told CNN in an email.

Furthermore, the authors “rightly note the importance of Indigenous knowledge, valorize pride of place, and defend territorial rights,” Heckenberger added.

The findings could prompt new archaeological expeditions to parts of the Amazon that have never been investigated before, extending “throughout the Amazonia in a wider area,” Peripato said. The probable existence of many thousands of pre-Columbian earthworks could also play a part in ongoing political debates in Brazil about land rights, he added, by confirming the historical presence of indigenous peoples in contested regions and bolstering their descendants’ claims to ancestral lands.

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.