Editor’s Note: Kate Schmier is a writer and editor whose fiction and nonfiction have been featured by NPR, Lilith Magazine, Alma, and others. She holds an MFA in writing from Sarah Lawrence College. The views expressed here are her own. Read more opinion on CNN.

When my husband Uri was finally sworn in as a US citizen in August, our announcement to loved ones was met with both excitement and trepidation. “I hope our country changes so that we can one day deserve a citizen like him,” one friend responded. “I wish we were in a better position to welcome him,” said another.

I understood their reservations: Uri has become an American amidst a pandemic that threatens our nation’s future, an administration that has repeatedly shown its hostility to immigrants, and a precipitous deterioration of our country’s global image. A recent Pew Research Center survey showed that international public opinion of the US is at a historic low.

Each day seems to bring fresh warnings that our democracy is in peril. And yet, when Uri took his oath of allegiance – wearing a mask and a face shield in a sweltering Manhattan courthouse – I found myself celebrating. Near the end of Uri’s ceremony, the judge reminded everyone in the courtroom that we are a nation of immigrants and thanked them for choosing the United States. I am forever grateful that Uri made this choice – and that so many others have, too.

Throughout our history, immigrants’ bravery, ingenuity and determination have enabled our country to progress towards its highest ideals and survive its darkest hours. By removing roadblocks for new citizens, especially around voting, we can mobilize individuals who could set our nation on a path to renewal.

I’m thrilled that Uri now has the chance to make his voice heard – and relieved by what his naturalization means for our family. For the majority of our 11 years together, I felt a looming sense of uncertainty and impermanence. Uri, a jazz saxophonist from Israel, told me soon after we met that there were no guarantees he would be able to stay.

Securing his artist’s visa – officially titled “Alien of Extraordinary Ability” – required massive amounts of paperwork, significant legal fees and many months of waiting and restricted travel. At one point, a snag in the application process kept him from leaving the country for almost two years. Even after the issue was resolved, I was on edge whenever he toured internationally. Every year, when his visa was up for renewal, I held my breath – afraid that this time, the bureaucrats reviewing his papers would decide to separate us.

Our marriage did not put an end to the uncertainty or to my anxiety. As a US-born citizen, I was able to sponsor Uri’s green card application. Almost a year after our wedding, we were summoned to the New York Field Office of US Citizenship and Immigration Services for the grueling green card interview – in which a couple must answer an immigration officer’s scrutinizing questions to prove their relationship isn’t a fraud.

We were counting on Uri’s lawyer to ensure it went smoothly, but he showed up nearly an hour late for our scheduled meeting. I wonder if the lawyer cared what his tardiness that morning might have cost us.

I thought of these uneasy moments when Uri finally got the call. The one telling him that, after 17 years in this country, he could stay for good. By that point, he had already passed his citizenship exam, but the last step – the oath ceremony – had been delayed since March due to Covid-19. In August, he and about 40 other immigrants from Ghana, Germany, China, and elsewhere were sworn in, standing six feet apart, by a judge who joined virtually.

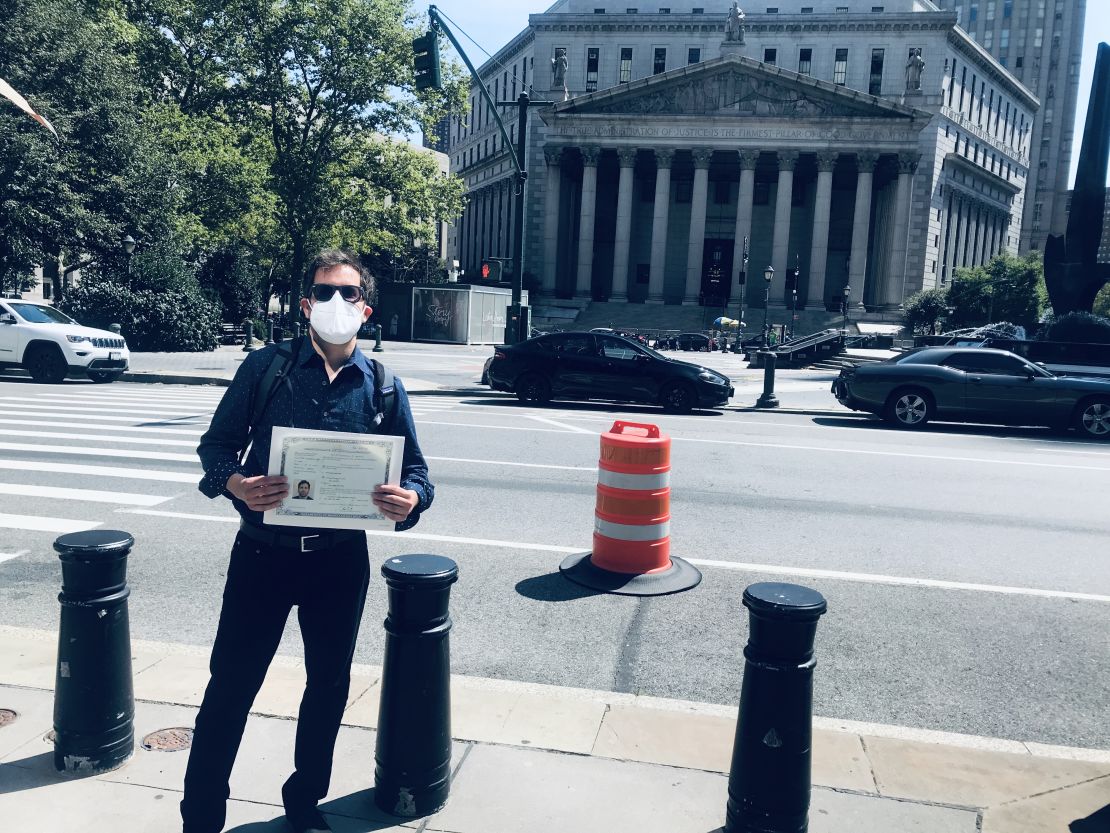

Family members weren’t allowed to attend, but Uri texted me a photo of himself holding his naturalization certificate in front of the New York County Supreme Court Building. For the first time, I was able to envision our long-term future in America.

The judge who administered Uri’s citizenship oath said something that helped me understand the broader significance of the moment: “This country is not perfect, but we have the power to change it.” It reminded me of new Americans’ potential to propel our nation forward. A recent report found that in many battleground states, the number of new Americans who are now eligible to vote is larger than the margin of victory in the 2016 elections – suggesting that newly naturalized citizens could strongly influence the outcome in November.

This is cause for optimism and hope, but time is running out. Voter registration deadlines are this week for more than a dozen states, passed last weekend in two others, and are fast approaching elsewhere. US Citizenship and Immigration Services has an urgent responsibility to expedite the naturalization process for pending cases.

While naturalizations tend to increase in an election year, hundreds of thousands may be disenfranchised due to the agency’s backlog of delayed oath ceremonies, civics tests and interviews. And despite President Donald Trump’s photo op with new citizens during the Republican National Convention, his new executive orders have further restricted immigration.

We must also remove barriers that prevent far too many naturalized citizens from fully participating in our democracy. Historically, immigrant voters have had lower turnout rates in presidential general elections than US-born voters. In 2016, according to Pew Research Center, 62% of US-born eligible voters cast a vote – compared with 54% of foreign-born voters.

One major obstacle is a linguistic one: While Uri was fortunate to come to this country with English proficiency, the Pew report found that nearly four-in-ten immigrant eligible voters say they speak English “less than very well,” which hinders civic engagement. Limited education and access to technology also create disenfranchisement, particularly in marginalized communities. Multi-pronged, multi-language outreach efforts targeting new citizens should become an even more significant part of “get out the vote” tactics, especially in swing states.

The power to change our country is not just about voting. Indeed, the United States has always relied on immigrants for new ideas and perspectives that drive innovation in the arts, sciences, and industry. I’ve seen this play out in my own life – from my ancestors who fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe and built thriving businesses in the Rust Belt to Uri’s community of talented musicians from across the globe.

I recall one memorable night, early in our relationship, when I accompanied Uri to a percussionist friend’s birthday party. In a crowded, dimly lit basement apartment in Harlem, immigrant musicians sang “Happy Birthday” in at least 10 different languages. I remember thinking this was the America I wanted to live in – one in which people from disparate backgrounds could come together for a common purpose. By empowering newcomers, we have the opportunity to make this vision a reality and save our nation’s future.