Editor’s Note: John Avlon is a CNN senior political analyst and anchor. The opinions expressed in this commentary are the author’s own. View more opinion articles on CNN.

Electoral College reform is suddenly all the rage. Elizabeth Warren endorsed abolishing the Electoral College in her CNN town hall. Beto O’Rourke and Kamala Harris soon joined the chorus. In response, President Donald Trump slammed the idea on Twitter – but back in 2012, he’d described the Electoral College as a “disaster for our democracy.”

So, is this simply a case of Democrats trying to change the rules after winning the popular vote but losing the presidency twice in two decades?

Is it an insult to the Founding Fathers’ original intent?

Or could it actually happen?

First of all, it turns out that this isn’t a new idea at all.

In fact, the Electoral College has been “targeted for reform or abolition some 700 times” over the course of our republic– more than any other part of the Constitution – wrote Jesse Wegman, a member of the New York Times editorial board. He is writing a book on the subject.

The Electoral College was the subject of intense debate among the Founding Fathers. They fought about it for months and didn’t settle on a plan until the very last days.

You might be surprised to find out that Constitution doesn’t say anything about letting you – the people – vote directly for president. It just says that a state’s electors – those representatives to the Electoral College – will do it on your state’s behalf…and that the state can basically choose any means of allocating those electors. That’s a bit disconcerting, and a reminder of how much of democracy is designed to be a work in progress.

Indeed, the Electoral College has not been a settled issue – at all. In fact, by 1823, James Madison, the former president and father of the Constitution, was railing against the inequities of the winner-take-all nature of the states’ electoral vote allocation.

In a letter to George Hay, Madison connected that system – which he’d grown to intensely dislike because it gave too much power to local political factions – with the rarely used provision that kicked a deadlocked presidential vote to the House of Representatives, where the presidency would be decided by state delegations, each having a single vote. This subversion of the will of the people he described as “evil at its maximum.”

One year later, Andrew Jackson won the popular vote but John Quincy Adams became president in the so-called corrupt bargain of 1824. That caused Sen. Thomas Hart Benton to rail against the winner-take-all system, calling it: “not a case of votes lost, but of votes taken away, added to those of the majority, and given to a person to whom the minority is opposed.”

That was the first of five times it’s happened in our history.

It happened next in the 1876 election, in what was a corrupt bargain to roll back Reconstruction – and again in 1888, which so incensed incumbent President Grover Cleveland that he ran again four years later to reclaim the office his supporters felt had been stolen from him.

This glitch wouldn’t happen again until the year 2000. That doesn’t mean there weren’t efforts to reform the Electoral College.

In fact, Indiana Sen, Birch Bayh, who died last week at age 91, came within a few votes of passing an amendment to abolish the Electoral College and replace it once and for all with a direct popular vote.

Beginning in 1966, Bayh argued that the president “should be elected directly by the people, for it is the people of the United States to whom he is responsible.”

By 1968, his once quixotic effort commanded 80% approval, according to a Gallup poll. That same year, segregationist George Wallace’s independent campaign came within 42,000 votes of forcing the presidential vote to the House of Representatives.

One year later, the House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly to abolish the Electoral College. Even President Richard Nixon was on board.

But the effort died in the Senate via an acute case of filibuster, thanks to a bloc by Southerners led by former Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond, who’d never been a big defender of counting every vote.

All this became semi-forgotten until the 2000 election – which George W. Bush won after the Supreme Court halted a recount along partisan lines.

That’s when a new idea began percolating – the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact.

Here’s how it would work: States pass legislation committing their Electoral College delegates to vote for the winner of the national popular vote. So far, 12 states have passed it – most recently Colorado – and the District of Columbia. And it’s gotten support from Republicans as well as Democrats in those states.

Here’s the thing: the compact wouldn’t kick in until the assembled states hit the requisite 270 electoral votes to deliver the presidency. And so the effort still has got a way to go, but Oregon, Maine and Nevada look like they may sign on next.

Even then this compact wouldn’t be a done deal. You can be sure it will face a court challenge – based on the right of the state to allocate the electors however it likes – that’s basically settled. Instead, the big question for the courts would be whether the compact itself is constitutional or whether it needs to go through congressional approval first.

Get our free weekly newsletter

The National Popular Vote Compact isn’t the only path to get to a popular vote. There’s also the constitutional amendment route, which looks unlikely given the polarization of the Senate. And there’s even a half measure possible, in which more states could split their electors, like Maine and Nebraska do now.

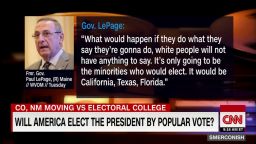

It’s likely that the drive for a national popular vote has gained new life because of Donald Trump: He lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million votes but won the Electoral College because of about 78,000 votes in three states. But the idea is not new. It’s been discussed and debated since James Madison strode the stage.

It’s back again, with renewed focus on how to make every American’s vote count equally for president.