Story highlights

Monkeys' hearts experienced some recovery after being treated with human embryonic stem cells

The research aims to clear several hurdles before it can go into human trials, including an apparent arrhythmia risk

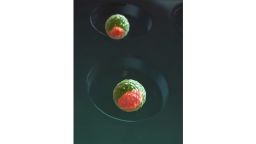

Following heart attacks, a handful of monkeys regained some of the pumping ability their hearts had lost after being given human embryonic stem cells, according to a study published Monday in Nature Biotechnology.

Scientists have tried for years to develop a stem cell treatment forheart disease caused by lack of blood flow, which contributed to more than 9.4 million deaths worldwide in 2016, according to the World Health Organization.

“We’re talking about the number one cause of death in the world [for humans],” said study author Dr. Charles Murry, director of the Institute for Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at the University of Washington. “And at the moment all of our treatments are … dancing around the root problem, which is that you don’t have enough muscle cells.”

After inducing heart attacks in macaques, the percent of blood their hearts pumped out with each beat dropped from roughly 70%, which is normal, to a weaker 40%. One month later, five monkeys who received human embryonic stem cells recouped 10.6 percentage points on average, versus only 2.5 in the control group.

Two of the monkeys continued to improve, and the others were euthanized one month after being given stem cells. They improved an additional 12.4 percentage points on average over the next two months.

However, some experts say the value of the new study may lie beyond these numbers, which come from just a handful of monkeys. Rather, it may come from how Murry’s team digs deeper into the irregular heartbeats that cropped up in a subset of these animals after receiving these stem cells.

“For the last several years, everybody’s been focused on why do we see these arrhythmias,” said John D. Gearhart, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and School of Veterinary Medicine. Gearhart, a former director of the university’s Institute for Regerative Medicine, was not involved in the new study.

“That is a very important observation because now you can perhaps begin to design a strategy to get at what is happening. How can we prevent this from happening?” Gearhart said. “And that totally, to me, is the story of this paper.”

Still, the prospect of a 10-point improvement is not insignificant to some doctors.

“That’s pretty impressive,” said Dr. Joseph Wu, director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute and a professor in the medical school’s departments of medicine and radiology. Wu was not involved in the new study.

“Additional studies will need to be done to further validate the concept before we go to clinical trials,” he said.

Skipping a beat

“Every morning when I wake up, this is number one on my mind. I eat, sleep, drink, breathe this arrhythmia thing right now,” Murry said. “We’ve got some very good ideas … but we haven’t got it sorted yet.”

One monkey in the study developed extensive arrhythmias starting 10 days after the stem cells were injected, lasting more than 20 hours per day. Another animal was excluded from the MRI analysis for this reason, as well. The study initially enrolled 17 monkeys but excluded eight “due to protocol design or complications … only one of which was related to cell treatment,” the authors wrote.

“It looks like the grafts that we’re putting in are behaving as biological pacemakers,” Murry said of his team’s findings.

“The heart functions on electrical currents. That means that anything you graft in … you have to get cells electrically coupled to other cells and thus beat in unison,” Gearhart said.

This is one problem Murry said his team must solve before they can achieve his goal of moving into early human trials by 2020. (Three of the study authors, including Murry, are scientific founders and hold stock in a company that plans to help fund later-phase clinical trials for this research.)

Another challenge is that these monkeys were on immunosuppressive drugs so that they didn’t reject the human donor cells. There is also a tumor risk, which Murry said he has not observed in heart trials.

Previous studies have shown that human embryonic stem cells improve heart function in smaller animals such as mice, rats and guinea pigs. But it has been unclear how the treatment would play out for larger animals like monkeys.

“Lots of people have cured mouse heart disease. That gets cured five times a year,” Murry quipped.

Still, experts point out that a macaque is still much smaller than a human adult, and it is unclear how this treatment would scale up in human trials.

“We’re always concerned about species differences among any organ and tissue that we have – and we find them,” Gearhart said. “And many times we ignore them to our own peril.”

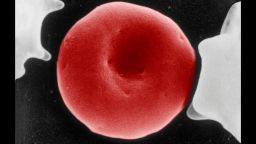

Tiny cells

The new study comes several years after a similar 2014 study by Murry’s group suggesting that human embryonic stem cells could regenerate primates’ heart muscle, but that study did not measure how well the heart could pump as a result.

Embryonic stem cells come from days-old embryos and thus have been the focus of political controversy. But their strength lies in their ability to differentiate into many types of cells, including “pure, bona fide” heart muscle cells, Wu said.

This is not the case with adult stem cells, which are present in everyone and can be gathered from places like the bone marrow, fat and the heart itself. These stem cells are thought to operate by secreting molecular signals to the surrounding heart, not by turning into heart muscle. And they eventually die off.

Previous research on the impact of adult stem cells on heart failure patients has suggested that these cells are not harmful to humans – but whether there’s a health benefit is less clear.

“In clinical trials,” Wu said, “overall these cells are quite safe, but at the same time we don’t see a dramatic improvement of cardiac function,” which is often measured in the percentage of blood a heart pumps out with each squeeze.

Despite the lack of definitive proof that this kind of therapy works in humans, direct-to-consumer clinics in the US and abroad offer unproven stem cell therapies. A 2017 survey of these clinics in the US that offer stem cell treaments for heart failure found that most of those who responded did not require medical records or employ a board-certified cardiologist. They charged an average of nearly $7,700 per treatment using a patient’s own stem cells and about $6,000 per treatment for donor cells.

The US Food and Drug Administration has cracked down on such clinics in the past, recently filing two federal complaints in May seeking to permanently ban two clinics from marketing stem cell products without regulatory approval. The agency accused them of “significant deviations” from good manufacturing practice requirements.

“I personally think it’s not a good idea to go to these clinics … and [get] injected with these stem cell therapies that have not been proven,” said Wu.

‘Progress’

The heart muscle “grafts” in Murry’s study averaged 11.6% of the size of the tissue damaged by cutting off its blood supply.

Over time, the monkeys’ new heart muscle cells appeared to develop, vascularize, and resulted in reduced scar size and better cardiac function, the study said.

“The heart has very little capacity to grow new cells” on its own, Gearhart said. Previous studies suggest that heart cells multiply at a pace of roughly 1% per year.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Some doctors remain uncertain that the cells in the new study had truly remuscularized the heart versus simply lingering from the procedure and impacting the surrounding cells.

Human embryonic stem cells have also been investigated in the US to treat spinal cord injuries and retinal degeneration, Murry said.

Gearhart said the paper is “an important contribution” and sees it as “progress, but it doesn’t resolve the issue.” But he remains hopeful.

“The heart is one of my loves – not to play on words,” Gearhart said.

CNN’s Susan Scutti contributed to this report.

Correction: This story has been updated to correct the spelling of Dr. Charles Murry’s name