Story highlights

Nairobi-based restaurant Gizani offers "Dining in the Dark" experience

Launched in May, the majority of its staff are visually-impaired

It’s a fine dining experience like no other. Cutlery scrapes against porcelain plates as diners delicately attempt to lift portions of classically prepared dishes to their mouths. The ambient sounds of conversations sing across the pitch black restaurant as an explosion of flavors engulf the tastebuds.

This heightened sensory dinner adventure is of course “Dans le noir” – or “Dining in the Dark” – but for Abdul Kamara, this is life.

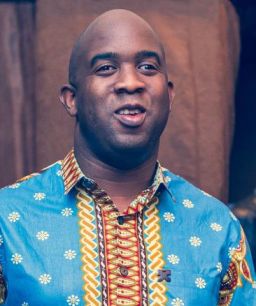

“The joke I often make with people is ‘Dining in the dark’ is just like everyday at home for me,” says the owner of Gizani in Nairobi – the first restaurant to offer up the well-established culinary trend in Africa.

“I’ve never had great sight,” explains Kamara, “but certainly by 2008, I’d lost almost all my sight. And so the only thing that remained was light perception. I have no functional vision at all.”

Not that the 35-year-old has ever let his visual impairment get in the way.

Originally from Sierra Leone, he studied abroad first in the U.S. and then the UK, where he came across the dining style he would later bring to the continent – the concept of eating in a darkened setting has been around for years with restauranteurs using the stimulating experience to bring awareness to the blind and visually-impaired. In recent times, the trend has spread from Europe to the U.S. and Far East.

“Friends and acquaintances who are blind or visually-impaired had actually experienced taking their clients to the ‘Dans le noir’ restaurant in central London. I was intrigued,” explains Kamara. “There are no examples of such an enterprise here on this continent (and) I thought Nairobi would be a great proving ground for it.”

Although he has a background in law and international development, Kamara decided against taking up another position in the sector when his family relocated to Kenya in 2013. Instead, he turned thoughts into action – and in the process is altering the perception of blindness to be more inclusive.

Out of the box thinking leads to positive change

“I saw it as an opportunity to see what impact (the concept) could have in the zeitgeist of Nairobi,” he explains. “Our guides are blind and for many of them this is a unique opportunity where they are able to be gainfully employed.”

He adds: “Normally we think of blind or disabled individuals, generally, as being dependents and non-contributing individuals. Their jobs are mostly within their families – washing the dishes, doing the laundry – but never actually bringing home the bacon.

“Here we actually have a shift of that dynamic – it’s extraordinary.”

Despite only running once a week at the Tribe Hotel, Kamara has welcomed over 400 diners since Gizani launched in late May. Kamara works with 11 visually-impaired staff and three sighted employees, who work front of house. But it’s been a steep learning curve.

“Opening a restaurant in Nairobi is hard enough – let alone one that’s in the dark,” he says.

Knowing he needed help, he asked a team from the “Dans le noir” group based in Paris to fly out and help teach his workforce. After an intense five-day period of training in procedure and operation – which plate to use, how to pour and other aspects of working in a five-star environment – his team had rapidly assimilated the knowledge required to wait tables.

“To say that they are waiters is something of an understatement because, really, they are guides. They walk you through the process, orient you to your environment and wait on you.”

With Gizani a growing attraction of Nairobi’s cosmopolitan culinary scene, Kamara says he feels humbled by the response from patrons.

“We’ve seen people come from around the East African region. There was even a couple from Kampala who flew here because they wanted to have the experience.”

He adds: “It brings a tear to my eyes. To know that this is something so well-received… I feel a sense of validation. I think that Africans have the same kind of issues about disability that many Westerners have. For me, I was just trying to find a way to test my own hypothesis, test other people’s assumptions and see if something like this could work.”

Photographs provided courtesy of EatOut Kenya.